Examining writing, arguments, communication, education, teaching, and ways of engaging with others.

Thursday, December 03, 2015

Tuesday, November 24, 2015

Scientists Discover Rhetoric!

Vox science reporter Brian Resnick posted on the topic of How We Argue when we argue about politics.

Specifically, Resnick wrote about what psychologists Feinberg and Willer found in their research on moral arguments.

When the discipline of rhetoric was developed about 2300 years ago, one of the most basic principles was the rhetorical triangle. During the two millenniums it's been in use, the rhetorical triangle has seen some changes, but the idea remains the same:

When the discipline of rhetoric was developed about 2300 years ago, one of the most basic principles was the rhetorical triangle. During the two millenniums it's been in use, the rhetorical triangle has seen some changes, but the idea remains the same:

There are a number of interactive factors that impact the way a message is heard, and if a person wants a specific message to influence a specific audience, all of those factors should be taken into consideration.

If you accept the principle above, then Feinberg and Willer's findings should not come as a surprise.

If you accept the principle above, then Feinberg and Willer's findings should not come as a surprise.

When you boil it down, those factors that influence how a message impacts an audience are the most important subjects of inquiry in Rhetoric & Composition.

It is what we do.

And we've been doing it pretty well for a long time.

So, sure, it is nice to see scholars in psychology confirm what has been the bedrock of our discipline for thousands of years.

So, sure, it is nice to see scholars in psychology confirm what has been the bedrock of our discipline for thousands of years.

That is exactly what researchers in psychology should do. No one in Rhetoric & Composition would dream of standing in the way of such helpful research. In fact, since the research procedure involved participants actually writing down their arguments, I hope maybe some of the studies' methods could make their way into my research.

But it is a bit troubling when a science reporter reports these findings as "new" to the broader public.

The findings may be new to the discipline of Social Psychology (and therefore worthy of publication in that discipline's journal), but the broader public should be aware of this.

"Should" is a key word here.

Part of the problem is that the discipline of Rhetoric & Composition has an ethos problem. People don't view the knowledge produced by the discipline as "knowledge" because we are rooted in the humanities. People want to see scientific inquiry, and that is something Social Psychologists can provide.

Another part of the problem is the discipline of Rhetoric & Composition hasn't always been the best at articulating its purpose.

And the final, perhaps most obvious point: While people should be aware of the impact of their own rhetorical choices, people forget, people get emotionally involved, people don't care, people love to hear themselves talk, etc...

Still, cool study.

Specifically, Resnick wrote about what psychologists Feinberg and Willer found in their research on moral arguments.

In a series of six studies, Willer and a co-author found that when conservative policies are framed around liberal values like equality or fairness, liberals become more accepting of them. The same was true of liberal policies recast in terms of conservative values like respect for authority.It's kind of funny that the research is reported as a new finding, because much of what Feinberg and Willer found describes the learning objectives of a strong writing program. Resnick frames their findings this way:

Whenever we engage in political debates, we all tend to overrate the power of arguments we find personally convincing — and wrongly think the other side will be swayed. On gun control, for instance, liberals are persuaded by stats like, "No other developed country in the world has nearly the same rate of gun violence as does America." And they think other people will find this compelling, too. Conservatives, meanwhile, often go to this formulation: "The only way to stop a bad guy with a gun is a good guy with a gun." What both sides fail to understand is that they're arguing a point that their opponents have not only already dismissed but may be inherently deaf to.

When the discipline of rhetoric was developed about 2300 years ago, one of the most basic principles was the rhetorical triangle. During the two millenniums it's been in use, the rhetorical triangle has seen some changes, but the idea remains the same:

When the discipline of rhetoric was developed about 2300 years ago, one of the most basic principles was the rhetorical triangle. During the two millenniums it's been in use, the rhetorical triangle has seen some changes, but the idea remains the same:There are a number of interactive factors that impact the way a message is heard, and if a person wants a specific message to influence a specific audience, all of those factors should be taken into consideration.

If you accept the principle above, then Feinberg and Willer's findings should not come as a surprise.

If you accept the principle above, then Feinberg and Willer's findings should not come as a surprise.When you boil it down, those factors that influence how a message impacts an audience are the most important subjects of inquiry in Rhetoric & Composition.

It is what we do.

And we've been doing it pretty well for a long time.

So, sure, it is nice to see scholars in psychology confirm what has been the bedrock of our discipline for thousands of years.

So, sure, it is nice to see scholars in psychology confirm what has been the bedrock of our discipline for thousands of years.That is exactly what researchers in psychology should do. No one in Rhetoric & Composition would dream of standing in the way of such helpful research. In fact, since the research procedure involved participants actually writing down their arguments, I hope maybe some of the studies' methods could make their way into my research.

But it is a bit troubling when a science reporter reports these findings as "new" to the broader public.

The findings may be new to the discipline of Social Psychology (and therefore worthy of publication in that discipline's journal), but the broader public should be aware of this.

"Should" is a key word here.

Part of the problem is that the discipline of Rhetoric & Composition has an ethos problem. People don't view the knowledge produced by the discipline as "knowledge" because we are rooted in the humanities. People want to see scientific inquiry, and that is something Social Psychologists can provide.

Another part of the problem is the discipline of Rhetoric & Composition hasn't always been the best at articulating its purpose.

And the final, perhaps most obvious point: While people should be aware of the impact of their own rhetorical choices, people forget, people get emotionally involved, people don't care, people love to hear themselves talk, etc...

Still, cool study.

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

First Year Composition and The Secret Formula

In January I will be teaching a first-year composition (FYC) course of my own design for the first time since early 2013.

FYC is the course that, way back in 2004, got me into my current profession.

It is a privilege to teach the course.

The entire idea behind FYC is awesome:

Introduce students to the knowledge and skills required to write while in college.

I aim to make this a strong course offering - one of my strongest yet.

And I'm excited to report I have found material for a new and (I believe) cool way to open the semester.

Well, I didn't find it. My colleague Professor Julian Heather recommended this podcast episode to me after reading one of my recent blog posts.

The podcast is called StartUp and the episode is called "The Secret Formula."

The premise of the episode is posted on StartUp's website:

It's an episode about creating an episode!

It's an episode about creating an episode!

As a composition instructor, the work that goes into creating a "text" is what I need students need to consider and explore.

The Secret Formula delivers great insights on pre-writing and putting together an initial draft, but it only gets better when they move on to some of the more difficult parts of writing: Revision & Editing.

There is a lot of useful material.

The podcast demonstrates the importance of collaboration via peer review. It shows just how helpful a critical reader can be during the revision process.

The makers of the podcast share early drafts of an episode and describe how and why they made changes.

There is constant attention on an imagined audience member.

The reality of shitty first drafts is explored (by someone other than Anne Lamott, who I admire greatly, but I've long needed to find at least one other person who has made that point about first drafts).

They even go into how the amount of work can sometimes seem like too much, but how that work pays off more often than not.

All that, and the episode is basically a massive reflective exercise. The podcast team spends much of their time examining what-works-and-why during the process of creating something for an audience, and then they work to abstract ideas from that reflection to better understand the broader process.

I'm a fan of Kathleen Blake Yancey's scholarship on reflection in the writing classroom, and it has shaped much of my approach to teaching. So, it's pretty cool to have a piece as accessible as this podcast to help me introduce those ideas to my students.

As a side note: The company producing the podcasts I wrote about today is called Gimlet Media. It was founded by one of the founders of the Planet Money podcast, something I've been listening to since 2008. That podcast has come up on this blog at least 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, times.

I really admire the work done by the people behind these podcasts, and I'm very happy to be able to use their work in my classroom.

FYC is the course that, way back in 2004, got me into my current profession.

It is a privilege to teach the course.

The entire idea behind FYC is awesome:

Introduce students to the knowledge and skills required to write while in college.

I aim to make this a strong course offering - one of my strongest yet.

And I'm excited to report I have found material for a new and (I believe) cool way to open the semester.

Well, I didn't find it. My colleague Professor Julian Heather recommended this podcast episode to me after reading one of my recent blog posts.

The podcast is called StartUp and the episode is called "The Secret Formula."

The premise of the episode is posted on StartUp's website:

Gimlet is making a big, expensive bet. The kind of bet that could make or break the company. And it’s a bet that comes down to one factor: What is Gimlet’s competitive advantage? As the company launches its fourth new show, “Surprisingly Awesome,” we take a deep dive in to how the show was made. From the kernel of an idea to the final product. And, along the way, we look at what we believe is Gimlet’s secret formula for making podcasts.

It's an episode about creating an episode!

It's an episode about creating an episode!As a composition instructor, the work that goes into creating a "text" is what I need students need to consider and explore.

The Secret Formula delivers great insights on pre-writing and putting together an initial draft, but it only gets better when they move on to some of the more difficult parts of writing: Revision & Editing.

There is a lot of useful material.

The podcast demonstrates the importance of collaboration via peer review. It shows just how helpful a critical reader can be during the revision process.

The makers of the podcast share early drafts of an episode and describe how and why they made changes.

There is constant attention on an imagined audience member.

The reality of shitty first drafts is explored (by someone other than Anne Lamott, who I admire greatly, but I've long needed to find at least one other person who has made that point about first drafts).

They even go into how the amount of work can sometimes seem like too much, but how that work pays off more often than not.

All that, and the episode is basically a massive reflective exercise. The podcast team spends much of their time examining what-works-and-why during the process of creating something for an audience, and then they work to abstract ideas from that reflection to better understand the broader process.

I'm a fan of Kathleen Blake Yancey's scholarship on reflection in the writing classroom, and it has shaped much of my approach to teaching. So, it's pretty cool to have a piece as accessible as this podcast to help me introduce those ideas to my students.

As a side note: The company producing the podcasts I wrote about today is called Gimlet Media. It was founded by one of the founders of the Planet Money podcast, something I've been listening to since 2008. That podcast has come up on this blog at least 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, times.

I really admire the work done by the people behind these podcasts, and I'm very happy to be able to use their work in my classroom.

Friday, November 13, 2015

Why the GOP is Getting Down

I sometimes worry my students will pick up bad habits by spending too much time with the public discourse.

You try to teach students how to argue with integrity and ethics, but eventually you have to let them watch a political debate on their own.

And that's a lot of what motivated this blog's on-and-off-again emphasis on rhetoric in the public discourse. When I see a bad argument that is effective, I want to sort out what's going on there. I've done it a few times.

In August of 2012, I wrote a post about the tone the GOP was using to describe the US. I argued the tone suggested the GOP had stopped believing in America. Truth told, I never thought the politicians making those arguments had actually stopped believing.

My liberal friends are going to be angry when I say this, but here goes, I don't think conservatives are dumb. I don't. I know a lot of smart conservative people. They don't see the world the same way I do, but if I assumed holding a different worldview made people dumb, then I'd be an asshole, wouldn't I?

No. Conservatives are no dumber (or smarter) than liberals, and back in 2012 they were looking at the same data I was. Back then I wrote:

Today, Ezra Klein noted how not much has changed.

In the piece, Klein uses data to push back against the "America is failing" campaign trail rhetoric.

And the data he uses is not wonky or difficult to parse.

So, what's the deal? Why do people make these claims?

Well, they work.

People want to be doing better. There are real issues the nation faces, and there is reason to push for changes.

But nuanced arguments about what it takes to hold onto gains made while making incremental changes to adjust for our nation's changing role in a global community in which--- ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ!!!!!

Right?

Donny "Yells-a-Lot" Trump is so much more fun than any of that.

Donny "Yells-a-Lot" Trump is so much more fun than any of that.

But is that the marker of good public discourse?

I don't think so. And it has a cost.

My sharpest students don't trust authority, and I applaud that. They shouldn't trust people who rely on smoke, mirrors, and boogeymen.

But they should also feel like they can sort through all the garbage and make an informed decision. Because eventually they are going to take up the role of authority and kick jokers like me to the curb.

I'm doing my best to help them out.

You try to teach students how to argue with integrity and ethics, but eventually you have to let them watch a political debate on their own.

And that's a lot of what motivated this blog's on-and-off-again emphasis on rhetoric in the public discourse. When I see a bad argument that is effective, I want to sort out what's going on there. I've done it a few times.

In August of 2012, I wrote a post about the tone the GOP was using to describe the US. I argued the tone suggested the GOP had stopped believing in America. Truth told, I never thought the politicians making those arguments had actually stopped believing.

My liberal friends are going to be angry when I say this, but here goes, I don't think conservatives are dumb. I don't. I know a lot of smart conservative people. They don't see the world the same way I do, but if I assumed holding a different worldview made people dumb, then I'd be an asshole, wouldn't I?

No. Conservatives are no dumber (or smarter) than liberals, and back in 2012 they were looking at the same data I was. Back then I wrote:

Despite the dreary picture the GOP would have us believe, the US is recovering faster than the rest of the developed world. While the EU attempted austerity, we stepped in with stimulus. We believed our economy was strong enough to risk that debt. Today, the EU faces inflation, rising borrowing costs, and no job growth. We, on the other hand, have dodged inflation, our borrowing costs have remained low, and we have slow job growth. (UK economists are starting to see it our way, btw.) Ours is clearly a dynamic economy that can weather very rough times. In relation to the rest of the world, our nation is a strong as ever.So back in 2012, I concluded that the 'down-on-America' talk was a scare tactic intended to win votes and justify cuts to proven programs the GOP was philosophically opposed to.

Today, Ezra Klein noted how not much has changed.

In the piece, Klein uses data to push back against the "America is failing" campaign trail rhetoric.

And the data he uses is not wonky or difficult to parse.

They would be surprised to find that unemployment is at 5 percent, America's recovery from the financial crisis has outpaced that of other developed nations, the percentage of uninsured Americans has been plummeting even as Obamacare has cost less than expected, and there's so much money flowing into new ideas and firms in the tech industry that observers are worried about a second tech bubble.One could make an argument that a stronger economy would be better (duh), but it is difficult to look at the major economic measures and reach the same dire conclusions we're hearing from conservative talking points.

So, what's the deal? Why do people make these claims?

Well, they work.

People want to be doing better. There are real issues the nation faces, and there is reason to push for changes.

But nuanced arguments about what it takes to hold onto gains made while making incremental changes to adjust for our nation's changing role in a global community in which--- ZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZZ!!!!!

Right?

Donny "Yells-a-Lot" Trump is so much more fun than any of that.

Donny "Yells-a-Lot" Trump is so much more fun than any of that.But is that the marker of good public discourse?

I don't think so. And it has a cost.

My sharpest students don't trust authority, and I applaud that. They shouldn't trust people who rely on smoke, mirrors, and boogeymen.

But they should also feel like they can sort through all the garbage and make an informed decision. Because eventually they are going to take up the role of authority and kick jokers like me to the curb.

I'm doing my best to help them out.

Thursday, November 05, 2015

Wednesday, October 28, 2015

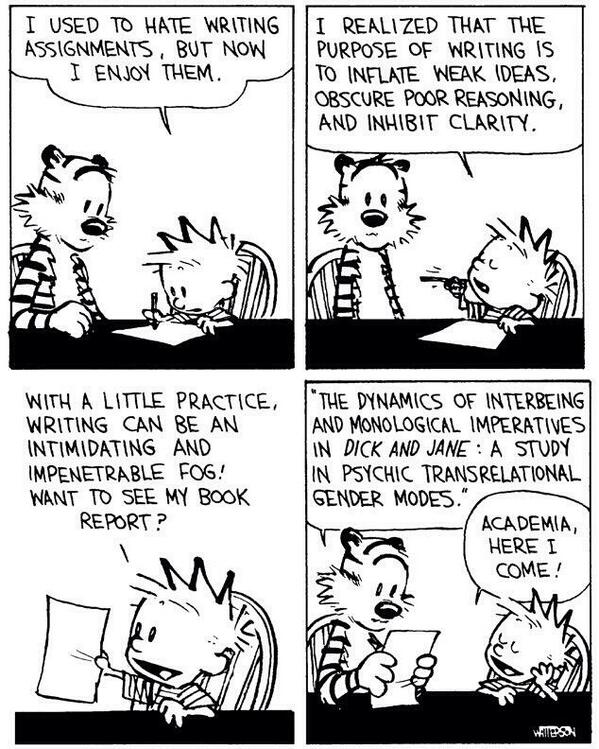

Dense Academic Prose

Victoria Clayton has a piece in The Atlantic on the complexity of academic writing.

It's an issue I deal with a lot because so much of the teaching I've done focuses on writing in the disciplines.

I have a lecture I do on hedging in academic writing, and it goes into some of the important reasons some sentences get cluttered. My students and I talk a lot about disciplinary jargon. The way we incorporate citations into sentences is a major concern as students advance in their studies. And the list goes on and on.

From a distance, academic writing often does look too complex. And sometimes it is. But I do worry about this debate. The debate suggests that there is one form of "Academic Writing," and that simply is not the case.

To a person who has examined writing across the disciplines, that suggestion is as silly as suggesting that there is one form of "writing for the public." Imagine if The Atlantic used the same style and tone as The Huffington Post or TMZ.

This article deftly deals with the complexities behind the styles of writing that emerge from academia.

It's an issue I deal with a lot because so much of the teaching I've done focuses on writing in the disciplines.

I have a lecture I do on hedging in academic writing, and it goes into some of the important reasons some sentences get cluttered. My students and I talk a lot about disciplinary jargon. The way we incorporate citations into sentences is a major concern as students advance in their studies. And the list goes on and on.

From a distance, academic writing often does look too complex. And sometimes it is. But I do worry about this debate. The debate suggests that there is one form of "Academic Writing," and that simply is not the case.

To a person who has examined writing across the disciplines, that suggestion is as silly as suggesting that there is one form of "writing for the public." Imagine if The Atlantic used the same style and tone as The Huffington Post or TMZ.

This article deftly deals with the complexities behind the styles of writing that emerge from academia.

A disconnect between researchers and their audiences fuels the problem, according to Deborah S. Bosley, a clear-writing consultant and former University of North Carolina English professor. “Academics, in general, don’t think about the public; they don't think about the average person, and they don't even think about their students when they write,” she says. “Their intended audience is always their peers. That’s who they have to impress to get tenure.” But Bosley, who has a doctorate in rhetoric and writing, says that academic prose is often so riddled with professional jargon and needlessly complex syntax that even someone with a Ph.D. can’t understand a fellow Ph.D.’s work unless he or she comes from the very same discipline.It is well worth the read, especially for students and scholars of writing.

Monday, October 26, 2015

Sunday, October 25, 2015

the highly scripted yet seemingly spontaneous ‘NPR Voice’

Great NYT piece on the rhetoric of the highly scripted yet seemingly spontaneous ‘NPR Voice’

Great NYT piece on the rhetoric of the highly scripted yet seemingly spontaneous ‘NPR Voice’ If I could attempt to transcribe it, it sounds kind of like, y’know … this.

That is, in addition to looser language, the speaker generously employs pauses and, particularly at the end of sentences, emphatic inflection. (This is a separate issue from upspeak, the tendency to conclude statements with question marks?) A result is the suggestion of spontaneous speech and unadulterated emotion. The irony is that such presentations are highly rehearsed, with each caesura calculated and every syllable stressed in advance.In a post I wrote a while back on the way conservative blogs and emails are formatted, I addressed this issue.

The observations made in the NYT point to yet another example of a community's readers shaping the style of discourse in unexpected ways. I'm fascinated at how technology pushes that process along at speeds that make the changes seem inevitable.

Read the whole article here: NYT

Thursday, October 22, 2015

Writing Reflecting in Reverse

I've set myself up for a difficult task here.

I'm asking my students to compose one reflective text for each of their writing projects in their portfolios. So, I'm providing them with a sample in which I do the thing I'm asking them to do. Only fair, right?

Writing a brief reflective introduction to something I wrote shouldn't be difficult, but I've made it difficult for myself. I'm reflecting on my dissertation: a large writing project that by the most conservative standards took five years for me to complete.

Why? Why would I pick that for this sample reflection?

Well, that word "complete" is a major factor here.

All of my writing is in varying stages of completeness, but this dissertation is the most complete text I've ever produced. I filed it with my university and said, "That's it. That is the final draft."

I'm asking my students to submit artifacts to their portfolios as "final drafts" (along with links to earlier drafts). So it's only fair that the most "final" draft I've produced to date should serve as my portfolio sample.

Now, if I selected this text because it has reached the final stage of the writing process, maybe that's where I should begin this reflection.

See, now that's weird. Just throwing the link to the final draft on the page and saying, "There it is!"

Doing that feels too easy. It was a huge process getting the thing done, which makes me want to tell the story behind the text, and I suppose that's what this reflection is meant to be...

And while it's nice to have this reflective space, it is not how most texts are experienced, right? People see the final product first.

I wanted to generate a table of contents, a list of tables, and a list of diagrams.

I wanted to dedicate it to my wife and kids.

I wanted to write up my acknowledgements.

I needed to get the pagination right.

I needed to convert it to a PDF.

I needed to submit it electronically for approval from grad studies.

I got all that done, but I will admit, actually going through the publication stage is very different from thinking about the publication stage.

But the later stages of editing felt important. Let me tell you one reason why.

Last spring the editor of Writing on the Edge David Masiel invited me to join him in an interview with Professor Kathleen Blake Yancey. I admire Professor Yancey and her work a great deal. Her most recent book, Writing Across Contexts, played an important role in my writing. I told her that after the interview. To which she responded: "Oh that's great. I look forward to reading it."

And that's when it really hit me. I was going to be producing a text for readers who A) are smarter and more accomplished than I am (e.g. my dissertation committee) and B) are potentially people who haven't read my work before.

I checked and re-checked things I hadn't really thought about in previous writings: the formatting of my diagrams and charts (especially the captions), the amount of times I used words I tend to overuse such as "however" (used 64 times in the final draft), paragraph indents, where pages ended, chapter numbering, and a bunch of other stuff.

I followed that with one last round of proofreading using Microsoft's 'text-to-speech' feature (highly recommended, btw).

Then the last step in editing was checking all of my references, making sure the in-text citations were clear and making sure the reference list was complete.

Even while I was drafting new chapters -- no, especially while I was drafting new chapters, I would have to go back and cut, reshape, move, or rewrite earlier passages. Then when I was done with the full first draft, I knew there was still a ton of re-working to do.

One writing-process choice sticks out: I would sit down and write for a while only to realize what I was working on didn't belong in the chapter or section I was drafting; it actually belonged in a section I hadn't yet written. So, while I was writing, there were always three or four paragraphs of to-be-placed material underneath where I was typing.

Then came reader feedback. I shared my work with Professor Dana Ferris first. She pointed out underdeveloped arguments and places where I mistakenly assumed my reader knew the literature as well as I did. I worked to address this while Professors Carl Whithaus and Lee Martin read. Their feedback helped me clear up terms and the theoretical framework.

I can't stress enough how much the feedback from experts moved the work forward. They are the ones who helped me understand how to re-shape my ideas for a broader community of scholars.

I'm asking my students to compose one reflective text for each of their writing projects in their portfolios. So, I'm providing them with a sample in which I do the thing I'm asking them to do. Only fair, right?

|

| Shortly after I filed my dissertation |

Why? Why would I pick that for this sample reflection?

Well, that word "complete" is a major factor here.

All of my writing is in varying stages of completeness, but this dissertation is the most complete text I've ever produced. I filed it with my university and said, "That's it. That is the final draft."

I'm asking my students to submit artifacts to their portfolios as "final drafts" (along with links to earlier drafts). So it's only fair that the most "final" draft I've produced to date should serve as my portfolio sample.

Now, if I selected this text because it has reached the final stage of the writing process, maybe that's where I should begin this reflection.

If I'm starting at the end,

then I suppose I should share the final draft here

at the begining...

at the begining...

Doing that feels too easy. It was a huge process getting the thing done, which makes me want to tell the story behind the text, and I suppose that's what this reflection is meant to be...

And while it's nice to have this reflective space, it is not how most texts are experienced, right? People see the final product first.

So, I'm writing this reflection in reverse...

Publication Stage

Just getting through the final stages of writing took so much longer than I thought. My committee had already signed off on the thing, which felt final, but there was still a ton to do.I wanted to generate a table of contents, a list of tables, and a list of diagrams.

I wanted to dedicate it to my wife and kids.

I wanted to write up my acknowledgements.

I needed to get the pagination right.

I needed to convert it to a PDF.

I needed to submit it electronically for approval from grad studies.

I got all that done, but I will admit, actually going through the publication stage is very different from thinking about the publication stage.

Editing Stage

Editing happened a lot during the writing process. I tend to complete a rough edit as I go, because every time I sat down to write, I had to read my way back into the project. I would fix and tinker with the text as I did this.But the later stages of editing felt important. Let me tell you one reason why.

Last spring the editor of Writing on the Edge David Masiel invited me to join him in an interview with Professor Kathleen Blake Yancey. I admire Professor Yancey and her work a great deal. Her most recent book, Writing Across Contexts, played an important role in my writing. I told her that after the interview. To which she responded: "Oh that's great. I look forward to reading it."

And that's when it really hit me. I was going to be producing a text for readers who A) are smarter and more accomplished than I am (e.g. my dissertation committee) and B) are potentially people who haven't read my work before.

I checked and re-checked things I hadn't really thought about in previous writings: the formatting of my diagrams and charts (especially the captions), the amount of times I used words I tend to overuse such as "however" (used 64 times in the final draft), paragraph indents, where pages ended, chapter numbering, and a bunch of other stuff.

I followed that with one last round of proofreading using Microsoft's 'text-to-speech' feature (highly recommended, btw).

Then the last step in editing was checking all of my references, making sure the in-text citations were clear and making sure the reference list was complete.

Revision Stage

This took for-f-ing-ever.Even while I was drafting new chapters -- no, especially while I was drafting new chapters, I would have to go back and cut, reshape, move, or rewrite earlier passages. Then when I was done with the full first draft, I knew there was still a ton of re-working to do.

One writing-process choice sticks out: I would sit down and write for a while only to realize what I was working on didn't belong in the chapter or section I was drafting; it actually belonged in a section I hadn't yet written. So, while I was writing, there were always three or four paragraphs of to-be-placed material underneath where I was typing.

Then came reader feedback. I shared my work with Professor Dana Ferris first. She pointed out underdeveloped arguments and places where I mistakenly assumed my reader knew the literature as well as I did. I worked to address this while Professors Carl Whithaus and Lee Martin read. Their feedback helped me clear up terms and the theoretical framework.

I can't stress enough how much the feedback from experts moved the work forward. They are the ones who helped me understand how to re-shape my ideas for a broader community of scholars.

Drafting Stage

This was messy. I spent months on the literature review, because my understanding of the literature is how I aimed to demonstrate a clear theoretical framework. So, I needed to work through that before writing up how I collected and analyzed any data. But I had to write up a proposal and submit it to IRB before that, and the proposal locked me into an agreement with the university on how I would proceed.

Yeah. This was messy. I'd love to provide a neat telling of the drafting, but my drafting process won't cooperate.

I blocked off hours of the day. Some days were productive. Some days were a total loss.

It's hard to write that last sentence. I have a wonderful wife and two great kids, and admitting that some days in my office were a waste makes me feel guilty.

But I'm not sure I would have completed the work without those days. Tiny but important breakthroughs happened at odd moments, and those led to the whole.

Yeah. This was messy. I'd love to provide a neat telling of the drafting, but my drafting process won't cooperate.

I blocked off hours of the day. Some days were productive. Some days were a total loss.

It's hard to write that last sentence. I have a wonderful wife and two great kids, and admitting that some days in my office were a waste makes me feel guilty.

But I'm not sure I would have completed the work without those days. Tiny but important breakthroughs happened at odd moments, and those led to the whole.

Pre-writing

I feel like this started years before I started grad school. In fact, my first chapter names 2004 as the year this project started.

My six years as a teacher in Budapest contributed to the shaping of this. My course work during the first three years of grad school was tremendously influential. My time at Transfer Camp got me ready to write.

In short, the project was so big that it is difficult to pinpoint where it began, but it did begin.

And now it's done.

Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Correct Grammar, but Bad Grammar Nonetheless

In an op-ed in today's New York Times, Ellen Bresler Rockmore writes about the Texas textbook debacle.

Rockmore examines how the textbook authors used grammar in unethical ways to meet the expectations of the Texas legislators who wanted to deemphasize the horrors of slavery.

Rockmore examines how the textbook authors used grammar in unethical ways to meet the expectations of the Texas legislators who wanted to deemphasize the horrors of slavery.The fact that Texas puts textbook choices in the hands of politicians makes me angry for so many reasons, but that's not why I'm writing.

Rockmore gracefully demonstrates how grammar is an important tool in crafting the public discourse.

She introduced an excerpt from one of the textbooks and went on to show where the book's grammar crosses an ethical line.

Some slaves reported that their masters treated them kindly. To protect their investment, some slaveholders provided adequate food and clothing for their slaves. However, severe treatment was very common. Whippings, brandings, and even worse torture were all part of American slavery.

Notice how in the first two sentences, the “slavery wasn’t that bad” sentences, the main subject of each clause is a person: slaves, masters, slaveholders. What those people, especially the slave owners, are doing is clear: They are treating their slaves kindly; they are providing adequate food and clothing. But after those two sentences there is a change, not just in the writers’ outlook on slavery but also in their sentence construction. There are no people in the last two sentences, only nouns. Yes, there is severe treatment, whippings, brandings and torture. And yes, those are all bad things. But where are the slave owners who were actually doing the whipping and branding and torturing? And where are the slaves who were whipped, branded and tortured? They are nowhere to be found in the sentence.It's an important point, and one that could help get people to stop yawning whenever I say, "Grammar."

Check out the whole article.

Thursday, October 15, 2015

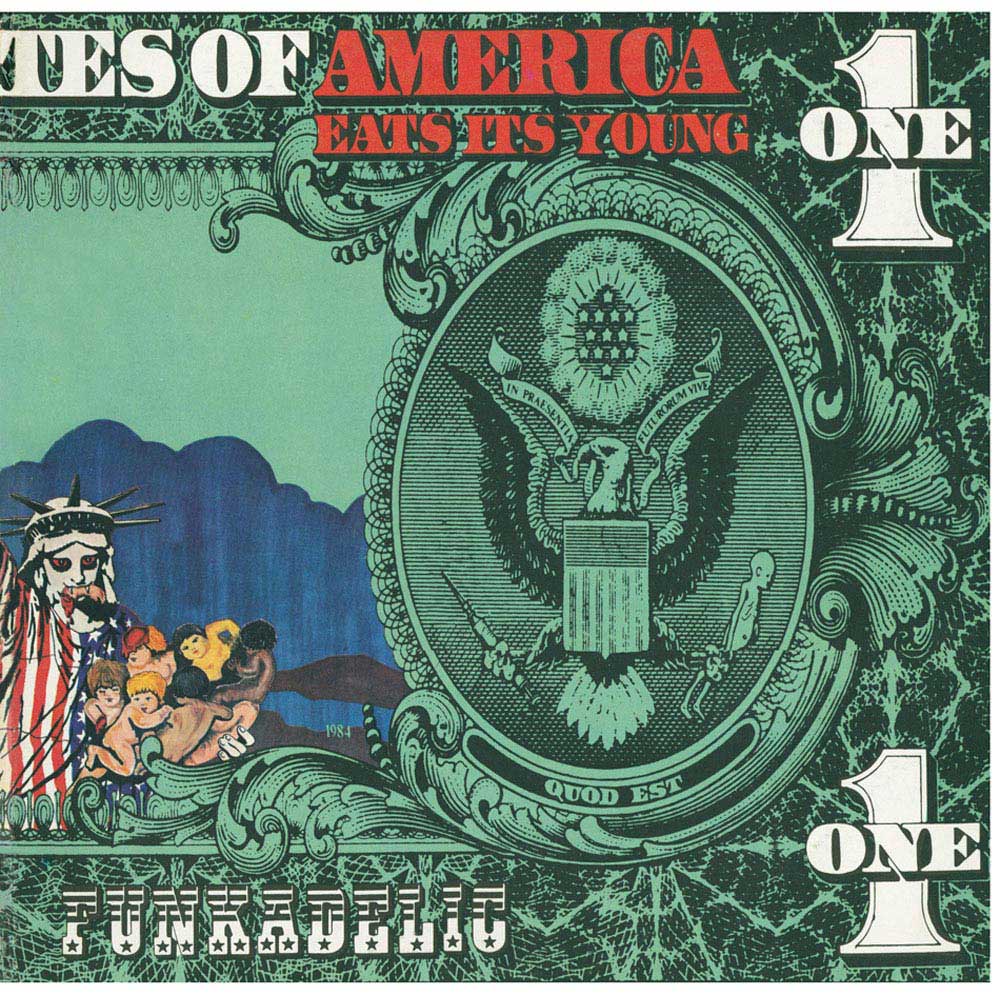

Is Rhetoric & Composition Eating Its Young?

In the last twelve months, I have learned there are at least three scholars in Rhetoric and Composition who do not believe I am a scholar of Rhetoric and Composition. One of those scholars told me there are a number of people in the discipline who feel this way.

That stings.

I identify as a scholar of Rhetoric and Composition.

It stings even more because the suggestion that I do not belong in the discipline comes from people I greatly admire -- people who have made important contributions to the field. In some cases it is people I know, people with whom I have discussed our discipline at length.

It turns out, for reasons I'll get to in this post, some scholars of Rhetoric and Composition want to exclude certain people from the discipline.

I am one such person. The reason for placing me outside of the disciplinary community is this: My doctorate was granted by a school of education, not by a department of Rhetoric and Composition.

You see, my degree is a "PhD in Education with an Emphasis in Writing, Rhetoric, and Composition Studies."

Just to be clear, that is the language on my diploma. So, the words "rhetoric" and "composition" are on the diploma, but admittedly, they are not the first words used to describe my degree.

The decision to pursue a degree with that title was mine. I wrestled with this question back when I applied to graduate programs.

When applying and later when picking which program I would attend (picking between the UC Davis program and a program with a PhD in Rhet/Comp), I researched this question: Is a "PhD in Education with an Emphasis in Writing, Rhetoric, and Composition Studies" a degree that scholars of rhetoric and composition will recognize?

The discipline's literature says "yes."

- Well-respected reviews of rhet/comp doctoral programs have included programs similar in structure and name to the one at UC Davis.

- The UC Davis program is included in the Doctoral Consortium in Rhetoric and Composition, a group created by scholars in NCTE, the professional organization I had joined to learn more about teaching writing.

- The same group listed programs like the one I attended in its rational for acknowledging rhetoric and composition as a discipline in its own right.

So, I looked at who I would be studying with at each of the programs that had accepted me. The experience and scholarship of the people at UC Davis impressed me a great deal. Both the writing program's director and the director of lower-division writing (a position I aspired to) offered to be my advisors. They made the choice easy.

I know I made the right call.

But I have been told multiple times now that a contingent of Rhetoric and Composition scholars believe my program choice means I cannot be acknowledged as a scholar of Rhetoric and Composition.

Now, this is not a "poor me" post. This perception of my program choice did not stop me from completing my degree in five years. It did not stop me from presenting at national conferences in the discipline. It did not stop me from composing a WAC/WID dissertation. It did not stop me from getting papers accepted for publication. Nor did it stop me from getting the job I wanted.

Some might suggest this is all reason enough to ignore the people who hold this exclusionary view, because they have clearly failed to keep me out of the discipline. But there's more to it than that. The community of scholars in Rhetoric and Composition is a small one, and many of the doctoral programs in Rhetoric and Composition use the "concentration" or "emphasis" model. Composition and Rhetoric is, after all, a discipline that works across several disciplinary boundaries.

So, a group of scholars seeking to exclude people based on a diploma's phrasing have an impact on the discourse community (a term taken from an applied linguist's work, btw).

Something I need to make clear here is this: The people who hold this exclusionary view are not mean people. There's good cause for people seeking to exclude some from the discipline. Let me explain:

In an extremely tight job market for tenure track jobs of any kind, there is a large pool of people who apply for any and every job, even jobs outside of their discipline. A number of people who pursue scholarship outside of rhetoric and composition have gained some experience teaching writing along the way. Some of these scholars believe this provides experience enough to obtain a tenure track job in Rhetoric and Composition. But all too often, these people have not studied or performed any research in the discipline. In the very legitimate interest of preserving those few precious tenure track spots for people who will contribute to the scholarship of Rhetoric and Composition, it is important to vet job candidates and recognize legitimate members of the disciplinary community.

I am not objecting to that practice.

I am, however, objecting to the very limited criteria used by people who would exclude scholars who can demonstrate disciplinary membership through their transcripts, mentors, scholarship, and professional associations.

I think I'm just asking people to avoid siloing our discipline away from its multidisciplinary roots -- read past the first five words on a diploma and acknowledge the contributions from young scholars seeking to grow our field's understanding of writing as a practice.

These kinds of exclusionary practices are troubling just 11 years after we had to go to the broader community of scholars and make a case for the disciplinarity of Rhetoric and Composition. It limits the work our field can accomplish. It is shortsighted and a waste of time. It makes us look bad.

I know I made the right call.

But I have been told multiple times now that a contingent of Rhetoric and Composition scholars believe my program choice means I cannot be acknowledged as a scholar of Rhetoric and Composition.

Now, this is not a "poor me" post. This perception of my program choice did not stop me from completing my degree in five years. It did not stop me from presenting at national conferences in the discipline. It did not stop me from composing a WAC/WID dissertation. It did not stop me from getting papers accepted for publication. Nor did it stop me from getting the job I wanted.

Some might suggest this is all reason enough to ignore the people who hold this exclusionary view, because they have clearly failed to keep me out of the discipline. But there's more to it than that. The community of scholars in Rhetoric and Composition is a small one, and many of the doctoral programs in Rhetoric and Composition use the "concentration" or "emphasis" model. Composition and Rhetoric is, after all, a discipline that works across several disciplinary boundaries.

So, a group of scholars seeking to exclude people based on a diploma's phrasing have an impact on the discourse community (a term taken from an applied linguist's work, btw).

Something I need to make clear here is this: The people who hold this exclusionary view are not mean people. There's good cause for people seeking to exclude some from the discipline. Let me explain:

In an extremely tight job market for tenure track jobs of any kind, there is a large pool of people who apply for any and every job, even jobs outside of their discipline. A number of people who pursue scholarship outside of rhetoric and composition have gained some experience teaching writing along the way. Some of these scholars believe this provides experience enough to obtain a tenure track job in Rhetoric and Composition. But all too often, these people have not studied or performed any research in the discipline. In the very legitimate interest of preserving those few precious tenure track spots for people who will contribute to the scholarship of Rhetoric and Composition, it is important to vet job candidates and recognize legitimate members of the disciplinary community.

I am not objecting to that practice.

I am, however, objecting to the very limited criteria used by people who would exclude scholars who can demonstrate disciplinary membership through their transcripts, mentors, scholarship, and professional associations.

I think I'm just asking people to avoid siloing our discipline away from its multidisciplinary roots -- read past the first five words on a diploma and acknowledge the contributions from young scholars seeking to grow our field's understanding of writing as a practice.

These kinds of exclusionary practices are troubling just 11 years after we had to go to the broader community of scholars and make a case for the disciplinarity of Rhetoric and Composition. It limits the work our field can accomplish. It is shortsighted and a waste of time. It makes us look bad.

Friday, October 09, 2015

Why do people opposed to gun control play the victim every time a group of innocent people get gunned down?

Why do people opposed to gun control play the victim every time a group of innocent people get gunned down?

So, I saw the uncorrected version this meme on social media. I checked the quote, because as a composition instructor I have a nose for quotes that seem a bit too on-the-nose.

Yeah. Turns out there is no record of GW saying this.

The meme is likely another example of someone realizing that no one is going to care about what some joker on Facebook has to say about the government or the right to bear arms. So, they falsely attributed it to someone with a bit more ethos.

The meme is likely another example of someone realizing that no one is going to care about what some joker on Facebook has to say about the government or the right to bear arms. So, they falsely attributed it to someone with a bit more ethos.

It's kind of like when someone opens by saying, 'according to studies, gun control has...,' but when pressed for specifics, they fail to find the name of any studies.

Or something I see even more often in the work of novice writers:

'It is widely known that gun control is a...' Oh I hate it when people tell me something debatable is "widely known."

But you see, we all want our arguments to sound important enough to merit attention. And there are some clever tricks for making an argument sound important.

But an ethical argument doesn't require tricks. An ethical argument stands on its own merit.

Knowing this doesn't make it any easier to compose an ethical argument. Nevertheless, this issue of slippery rhetorical tactics is something I work to make my students aware of. These methods of argument are so common that students might not even know when they themselves are using them.

But these techniques have consequences. People start to misunderstand history, devalue the reliability of the sciences, or misconstrue public policy.

For example, when I pointed out in a comment that the above quote was not spoken by George Washington, the original poster responded by saying, "if it was up to non-pro gun owers, we wouldn't have anything. Anyway, yes we do keep our rights and as far as I'm concerned they have not EXPANDED they take more and more EVERY chance they get."

What's odd here (other than the unintentional support of my point via unclear pronoun usage) is this is a gun enthusiast who actually believes his rights are constantly being eroded.

That just isn't the case. As of 2013, people can now carry a concealed weapon in all 50 states. Assault rifles are legal in all but 7 states. States are changing laws so that formally gun-free campus allow students to carry weapons.

We live in country where gun control is being relaxed.

That does not seem to register with people who are are against gun control. Pro-gun folks roll out the rhetoric of the persecuted whenever gun violence is in the news. They talk about dictators and looming threats.

And whenever a mass shooting pushes the nation to question our decisions to continually relax gun control, the pro-gun crowd convinces themselves that they are the victims.

Don't talk about an assault rifle ban, or else you'll hear them gasp, "How dare you threaten the right our forefathers fought for and that we won in 2004."

The effort has worked. In the minds of many this modern policy debate is linked to a caricature of our forefathers, or else it is portrayed as an assault on the persecuted.

It's absurd, and it's in particularly bad taste to play victim every time innocent people have been shot.

And so, I call on you to stop putting up with it:

If they start acting like victims, here's what you should do:

|

| A quote falsely attributed to George Washington with my less-than-clever speech bubble |

Yeah. Turns out there is no record of GW saying this.

The meme is likely another example of someone realizing that no one is going to care about what some joker on Facebook has to say about the government or the right to bear arms. So, they falsely attributed it to someone with a bit more ethos.

The meme is likely another example of someone realizing that no one is going to care about what some joker on Facebook has to say about the government or the right to bear arms. So, they falsely attributed it to someone with a bit more ethos.It's kind of like when someone opens by saying, 'according to studies, gun control has...,' but when pressed for specifics, they fail to find the name of any studies.

Or something I see even more often in the work of novice writers:

'It is widely known that gun control is a...' Oh I hate it when people tell me something debatable is "widely known."

But you see, we all want our arguments to sound important enough to merit attention. And there are some clever tricks for making an argument sound important.

But an ethical argument doesn't require tricks. An ethical argument stands on its own merit.

Knowing this doesn't make it any easier to compose an ethical argument. Nevertheless, this issue of slippery rhetorical tactics is something I work to make my students aware of. These methods of argument are so common that students might not even know when they themselves are using them.

But these techniques have consequences. People start to misunderstand history, devalue the reliability of the sciences, or misconstrue public policy.

For example, when I pointed out in a comment that the above quote was not spoken by George Washington, the original poster responded by saying, "if it was up to non-pro gun owers, we wouldn't have anything. Anyway, yes we do keep our rights and as far as I'm concerned they have not EXPANDED they take more and more EVERY chance they get."

What's odd here (other than the unintentional support of my point via unclear pronoun usage) is this is a gun enthusiast who actually believes his rights are constantly being eroded.

That just isn't the case. As of 2013, people can now carry a concealed weapon in all 50 states. Assault rifles are legal in all but 7 states. States are changing laws so that formally gun-free campus allow students to carry weapons.

We live in country where gun control is being relaxed.

That does not seem to register with people who are are against gun control. Pro-gun folks roll out the rhetoric of the persecuted whenever gun violence is in the news. They talk about dictators and looming threats.

And whenever a mass shooting pushes the nation to question our decisions to continually relax gun control, the pro-gun crowd convinces themselves that they are the victims.

Don't talk about an assault rifle ban, or else you'll hear them gasp, "How dare you threaten the right our forefathers fought for and that we won in 2004."

The effort has worked. In the minds of many this modern policy debate is linked to a caricature of our forefathers, or else it is portrayed as an assault on the persecuted.

It's absurd, and it's in particularly bad taste to play victim every time innocent people have been shot.

And so, I call on you to stop putting up with it:

Gun rights advocates are not victims.

Don't let them act like they are.If they start acting like victims, here's what you should do:

- Point out that they are acting like the victim when the real victims are the ones who got shot.

- Tell them to stop whining. It's just unbecoming.

- Ask them to describe how and when exactly their right to bear arms have been violated. Make them be specific. Ask them about their rights. Ask if they have been forced to give up a gun. Ask if they missed a hunting trip or a day on the range due to unreasonable waiting periods.

- And don't put up with any nonsense. Gun owners have their rights, and any suggestion otherwise is stupid.

Wednesday, October 07, 2015

Tuesday, September 29, 2015

A tiny and deeply contextualized victory

On day one I had a student get up in my face.

I had suggested the style endorsed by the MLA isn't particularly useful unless you're writing literary analysis (because it isn't).

The student was aghast. He was good humored about it, but he didn't like hearing anything but praise for MLA style.

While those are not exactly fighting words, I actually appreciated the challenge.

It gave me a chance to explain why I prefer the social-science-friendly APA style when writing papers in composition and rhetoric.

The student listened politely, but he was not convinced. He is an English major, and MLA has worked perfectly well all this time.

The student listened politely, but he was not convinced. He is an English major, and MLA has worked perfectly well all this time.

We agreed to disagree...

Until today!

The course is a senior seminar, and we're investigating questions about writing skill transfer. Today we read Wardle's article "Mutt Genres."

As has often happened in this course, the students began discussing the following: The style of writing that has served them well for years in literature courses does not transfer very effectively when writing for other disciplines. This discussion typically revolves around concision. Other disciplines want more concision than these students are accustomed to.

One student referred to how "Mutt Genres" was concise, but claimed even that article could be trimmed down.

I challenged the student to point out something worth trimming in the article.

From the other side of the classroom, the student who had scoffed at my criticism of MLA style chimed in: "You know what could be cut, all the names of all the authors jammed into every sentence."

The student was referring to all of the references in Wardle's well-researched lit review.

And I had him!

You see, in MLA style, the first time you use an author's name in a sentence, you are expected to use both the author's given name and family name. When writing about literature, this convention is actually kind of nice. But that same convention is cumbersome when writing for a community that expects a paper to be loaded up with citations (looking at you, social sciences).

Mutt Genres" was published in College Composition and Communication, a journal that (frustratingly) requires authors to abide by the conventions of MLA style.

And I made a show of winning this battle.

I let the student know with a, "So, you're saying that there may be some scholarly genres that don't suit the MLA style?!?!?"

He conceded defeat, and I actually raised my arms in triumph.

Yes. It is a tiny and deeply contextualized victory, but it is my tiny and deeply contextualized victory.

I had suggested the style endorsed by the MLA isn't particularly useful unless you're writing literary analysis (because it isn't).

The student was aghast. He was good humored about it, but he didn't like hearing anything but praise for MLA style.

While those are not exactly fighting words, I actually appreciated the challenge.

It gave me a chance to explain why I prefer the social-science-friendly APA style when writing papers in composition and rhetoric.

The student listened politely, but he was not convinced. He is an English major, and MLA has worked perfectly well all this time.

The student listened politely, but he was not convinced. He is an English major, and MLA has worked perfectly well all this time.We agreed to disagree...

Until today!

The course is a senior seminar, and we're investigating questions about writing skill transfer. Today we read Wardle's article "Mutt Genres."

As has often happened in this course, the students began discussing the following: The style of writing that has served them well for years in literature courses does not transfer very effectively when writing for other disciplines. This discussion typically revolves around concision. Other disciplines want more concision than these students are accustomed to.

One student referred to how "Mutt Genres" was concise, but claimed even that article could be trimmed down.

I challenged the student to point out something worth trimming in the article.

From the other side of the classroom, the student who had scoffed at my criticism of MLA style chimed in: "You know what could be cut, all the names of all the authors jammed into every sentence."

The student was referring to all of the references in Wardle's well-researched lit review.

And I had him!

You see, in MLA style, the first time you use an author's name in a sentence, you are expected to use both the author's given name and family name. When writing about literature, this convention is actually kind of nice. But that same convention is cumbersome when writing for a community that expects a paper to be loaded up with citations (looking at you, social sciences).

Mutt Genres" was published in College Composition and Communication, a journal that (frustratingly) requires authors to abide by the conventions of MLA style.

And I made a show of winning this battle.

I let the student know with a, "So, you're saying that there may be some scholarly genres that don't suit the MLA style?!?!?"

He conceded defeat, and I actually raised my arms in triumph.

Yes. It is a tiny and deeply contextualized victory, but it is my tiny and deeply contextualized victory.

Friday, September 25, 2015

Friday, September 18, 2015

On a Graceful Description of a Crucial Aspect of My Discipline

About a month before my graduation ceremony last June, my dad finally got around to asking a

About a month before my graduation ceremony last June, my dad finally got around to asking a potentially awkward question: "So, what exactly does it mean to be a professor of composition & rhetoric?"

It sounds worse than it actually is - that my dad only got around to asking about my discipline as I was closing in on a Ph.D.

It's a question practitioners of my discipline should be actively answering more often.

A lot of people have this question about comp/rhet. In fact, on day one of the comp/rhet seminar I'm leading this semester, one student had the wisdom/candor to ask the same question.

I think I did an okay job of answering the question on both occasions.

I described the Aristotelian roots of rhetoric as a discipline. Both my dad and my students understood that. As a starting point it particularly pleased my dad, because it vindicates my choice to major in philosophy as an undergrad (a choice he always supported).

I went on to describe a still-growing appreciation for the study of how different communities compose texts.

I used that to situate my interest in how students learn to write for various academic and professional communities.

I finished by explaining my dissertation's examination of resources in biology courses that help students learn to write like biologists.

My dad got it, and that felt good. My students actually seemed interested, which was important.

I'll tell you what I didn't describe: I didn't go into the four decades of upheaval and dramatic change that have impacted the teaching of writing at colleges across the country. It's an important part of the conversation, but I often steer clear of the subject. It seems too fraught with the pitfalls of university politics and endless arguments about the function of a college education.

This summer, however, Ed White demonstrated how to tackle this complex issue with grace and concision. I shouldn't be surprised. Everything I've read by White has led to a deeper understanding of my discipline. "What on Earth Has Happened to Freshman English?" however, is especially impressive. In under 800 words, White explains a massive shift in the approach to teaching writing in college. He does not oversimplify, but he also avoids getting bogged down by potentially distracting details.

The first-year course, no longer freshman English and more and more removed from English literature (in some institutions, from the English department as well), is now first-year composition (FYC) and often only one part of an extensive writing program extending from placement testing of entering students and a range of required first-year writing courses to upper-division writing requirements—often under the purview of a writing across the curriculum or a writing in the disciplines program and supported by a university writing center—and senior capstone courses usually involving writing in the major. The teaching of writing has recognized that most writing in this century is done in a technological environment and many classes submit work online, where peer review of early drafts is common, revision is routine, and e-portfolios determine final grades. And that first-year writing course, now well correlated with student success in college, is much more concerned with helping all students succeed than with getting rid of the unprepared.I can't recommend the entire essay enough.

Thursday, August 27, 2015

Meta-syllabus

So, I think I finished the course description for my College Composition II course. I've finally gotten to a place where I am comfortable writing the syllabus I've always wanted to write. Let me know what you think.

Oh, wow, are you asleep yet?

Look, I’m going to drop the academic tone for a second here. Don’t get me wrong, I like academic writing, and I sincerely hope you develop enthusiasm for the work we do in this class, but I don’t think all of my students are as into the “situational nature of the standards” as I am. And that's fine. You don't need to be enthusiastic about composition to get at the purpose of this course.

I’ll admit, this attempt at straight talk in a syllabus is a ploy. I’m breaking the rule of a familiar genre in an attempt to establish my voice, generate a rapport, and deal with the elephant in the room: A lot of my students would not be in my class were it not for a university requirement. In my discipline, this kind of obstacle is referred to as a constraint – a factor that makes it difficult to achieve my goal.

And what is my goal here? I’m going to answer that in this paragraph, but before I do, you should try and answer the question. Take your time. Got an answer? Okay. Here’s my purpose: I want this section of the syllabus to introduce the goals of this course and then demonstrate the methods we’ll use to achieve those goals. So, how’d you do? Do our answers match? If so, why do you think that is. If not, why? That was your first course activity. Achievement unlocked!

So, we’re going to examine how writing does the things it does. More specifically, we’re going to look at the things writing needs to do as you work on general education requirements and courses for your major.

So, we’re going to examine how writing does the things it does. More specifically, we’re going to look at the things writing needs to do as you work on general education requirements and courses for your major.

Back to the catalog: “Students will research and analyze different disciplinary genres, purposes, and audiences with the goals of understanding how to appropriately shape their writing for different readers and demonstrating this understanding through various written products.”

Course Description

From the Course Catalog: “An advanced writing course that builds upon the critical thinking, reading, and writing processes introduced in English 1A, 2, 5, or 10/11. This class emphasizes rhetorical awareness by exploring reading and writing within diverse academic contexts with a focus on the situational nature of the standards, values, habits, conventions, and products of composition…”Oh, wow, are you asleep yet?

Look, I’m going to drop the academic tone for a second here. Don’t get me wrong, I like academic writing, and I sincerely hope you develop enthusiasm for the work we do in this class, but I don’t think all of my students are as into the “situational nature of the standards” as I am. And that's fine. You don't need to be enthusiastic about composition to get at the purpose of this course.

I’ll admit, this attempt at straight talk in a syllabus is a ploy. I’m breaking the rule of a familiar genre in an attempt to establish my voice, generate a rapport, and deal with the elephant in the room: A lot of my students would not be in my class were it not for a university requirement. In my discipline, this kind of obstacle is referred to as a constraint – a factor that makes it difficult to achieve my goal.

And what is my goal here? I’m going to answer that in this paragraph, but before I do, you should try and answer the question. Take your time. Got an answer? Okay. Here’s my purpose: I want this section of the syllabus to introduce the goals of this course and then demonstrate the methods we’ll use to achieve those goals. So, how’d you do? Do our answers match? If so, why do you think that is. If not, why? That was your first course activity. Achievement unlocked!

So, we’re going to examine how writing does the things it does. More specifically, we’re going to look at the things writing needs to do as you work on general education requirements and courses for your major.

So, we’re going to examine how writing does the things it does. More specifically, we’re going to look at the things writing needs to do as you work on general education requirements and courses for your major.Back to the catalog: “Students will research and analyze different disciplinary genres, purposes, and audiences with the goals of understanding how to appropriately shape their writing for different readers and demonstrating this understanding through various written products.”

Monday, August 24, 2015

Metacognition and the Hook

As of today, I have joined a new department at a new university, and as is often the case, the politics of the place are messy and daunting. And that was where my head was at after day one of orientation.

But as Hemingway once had one of his drunk characters say, "Never be daunted."

And in that spirit, I had a few beers, went on a dog walk, and sketched out part of the opening week in my advanced composition course.

I'm looking to get my students to break down some of the core concepts needed to talk about writing. I want them to use their experience and prior understandings to define terms like "discourse community," "genre," "rhetoric," "audience," and "metacognition."

I'm looking to get my students to break down some of the core concepts needed to talk about writing. I want them to use their experience and prior understandings to define terms like "discourse community," "genre," "rhetoric," "audience," and "metacognition."

But I won't pretend those are easy terms to define. Like any abstract concept, these terms will only take root if the denotative definition can be paired with concrete examples, right?

And that is what inspired me to start off a lecture with Blues Traveler's 1994 song, Hook.

Okay, I'll admit it; the song came up on a Spotify playlist, but it does work as a point of entry for a lesson on metacognition.

And it's fun to use a song from my freshman year of college to introduce my students to one of my course's core concepts.

Well, whatever prompted the song's use, it is shaping up to be a nice little intro to the idea of thinking about your own process.

But as Hemingway once had one of his drunk characters say, "Never be daunted."

And in that spirit, I had a few beers, went on a dog walk, and sketched out part of the opening week in my advanced composition course.

I'm looking to get my students to break down some of the core concepts needed to talk about writing. I want them to use their experience and prior understandings to define terms like "discourse community," "genre," "rhetoric," "audience," and "metacognition."

I'm looking to get my students to break down some of the core concepts needed to talk about writing. I want them to use their experience and prior understandings to define terms like "discourse community," "genre," "rhetoric," "audience," and "metacognition."But I won't pretend those are easy terms to define. Like any abstract concept, these terms will only take root if the denotative definition can be paired with concrete examples, right?

And that is what inspired me to start off a lecture with Blues Traveler's 1994 song, Hook.

And it's fun to use a song from my freshman year of college to introduce my students to one of my course's core concepts.

Well, whatever prompted the song's use, it is shaping up to be a nice little intro to the idea of thinking about your own process.

Friday, August 14, 2015

Punchy as Things Wrap

On Wednesday I taught the last lecture at my current institution before I move on to Sac State. So, I might be a little punchy. But for the most part I've been holding myself in check.

Until...

Well, it's a three-lecture series for visiting international students doing research in the STEM disciplines. The students are all exceptional and have expressed interest in graduate studies.

Today the students should submit a draft statement of purpose (SOP) for grading (this is after Wednesday's peer-review workshop).

One student wrote today and explained that the SOP task required too much time and he likely wouldn't be able to complete it. Five minutes later he wrote and asked for an extension.

I replied:

Hi,

As of today, you've had 10 days to do the work of researching the school and writing the PS. How much more time do you think you need?

HMH

The student wrote back:

Ok I will turn in the homework. But I want to emphasize that I need to spend most of my time doing the lab work. Do you think your writing is so important? I'm not incapable of doing any courses or homework you have. I'm just uncomfortable with your attitude.

So, here's what I had to say about that:

[Student's first name],

If my attitude caused you some discomfort, please know that was not my intention.

I was asked by the organizers of the ****** program to develop two assignments along with lectures/workshops to accompany those assignments:

1) An abstract

2) A statement of purpose

The organizers of the program that you signed up for decided these tasks were important.

They probably decided this because familiarity with those two writing tasks can be useful for undergrads seeking to pursue graduate studies in the STEM disciplines.

Do I think these writing tasks are "so important"?

No. Not really. Your personal statement for admission to graduate school is not important to me. If you don't complete the task, it will not impact my life at all.

Do you think writing a strong personal statement is important?

Do you think the grade associated with this assignment is important.

If the answer to either of these questions is yes, please complete the task. If not, forget about it. You seem to have more important things to do.

If you just need extra time, please take a few extra days. I did ask how much time you needed, but since you didn't answer, here's my schedule: I won't be done grading these until next week. I'm not going to penalize late submissions, but I will not accept submissions after 8/18. Like I said, if you decide not to write it, that's fine. I'll just score the task as a zero. Not a big deal.

If you decide to write the personal statement, please consider this advice:

Think about your writing situation more carefully than you did when you wrote your last email. Let me explain; you had recently asked me for an extension of a deadline. I responded by asking how much time you needed. In your follow-up email, you questioned the importance of the task I assigned and then suggested my attitude made you uncomfortable. That's a pretty antagonistic stance to take after making a request. If I had a personal stake in your request, your tone might have led me to deny it. But that's not the attitude I have about this situation. It is, however, the attitude a member of an admissions committee might have when deciding whether or not they want you to join their department. So, for your personal statement, you should probably work on developing a tone that demonstrates a bit more respect for your reader.

Let me know what you decide to do. Or don't. I also have other priorities that rank higher than this.

I wish you the best,

HMHJust before posting this I received an apology from the student. He explained his research project isn't going as planned and he's under a lot of stress as a result. I think our instructor/student relationship is back on track... So, maybe my snarky response is what this situation called for?

I don't know, but please don't judge the student too harshly.

Saturday, July 18, 2015

Presented at #CWPA2015 and shared ideas from the dissertation

This morning I presented some of the larger ideas from my dissertation.

I presented alongside two other scholars.

Ryan Roderick is a PhD student at Carnegie Mellon, and he presented his findings from a corpus linguistics study that compared the "ways of doing" in a large number of texts from across 16 different disciplines.

Drew Scheler is a professor and the director of the WAC program at Saint Norbert College. He presented on how faculty survey data can be used to generate support and community for a writing program.

I enjoy the session quite a bit.

Here is my Prezi from the session.

My goal was to demonstrate how researchers could map out the writing environments our student are going to encounter after they complete our writing courses.

Let me know what you think.

I presented alongside two other scholars.

Ryan Roderick is a PhD student at Carnegie Mellon, and he presented his findings from a corpus linguistics study that compared the "ways of doing" in a large number of texts from across 16 different disciplines.

Drew Scheler is a professor and the director of the WAC program at Saint Norbert College. He presented on how faculty survey data can be used to generate support and community for a writing program.

I enjoy the session quite a bit.

Here is my Prezi from the session.

My goal was to demonstrate how researchers could map out the writing environments our student are going to encounter after they complete our writing courses.

Let me know what you think.

Thursday, June 25, 2015

WTF, Marc and The President

It took me some time to get around to listening to this, but on the dog walk tonight I listened to the episode of Marc Maron's WTF podcast in which he spends an hour chatting with President Obama.

It took me some time to get around to listening to this, but on the dog walk tonight I listened to the episode of Marc Maron's WTF podcast in which he spends an hour chatting with President Obama.I know people got all excited about a word or two the President said, but man, are they missing the point.

This podcast is phenomenal, and I get to say that here because the two of them devote several minutes to discussing how we argue.

I cannot recommend the episode enough.

Tuesday, June 23, 2015

Borowitz's Thoughts about Idiots

The New Yorker published this gem from Andy Borowitz today.

And yeah, it is frustrating (and exhausting) when overwhelming evidence fails to convince people of an argument's validity, but that just means we haven't put together the right argument yet.

According to the poll, conducted by the University of Minnesota’s Opinion Research Institute, while millions have been vexed for some time by their failure to explain incredibly basic information to dolts, that frustration has now reached a breaking point.