This fall I've been working on a new method for delivering comments on drafts of student papers.

I should mention, I'm not grading the drafts when I use this new method. I provide this feedback so my students can revise

before turning stuff in for a grade. In my courses, this is the most extensive feedback I give.

This method-in-development has helped me deal with two issues I face when writing back to students.

Improving Feedback Clarity

Like many teachers, I have trouble knowing what students will take away from my feedback.

Some students read every comment. Some never read any at all. Some read too much into one comment and ignore the rest. Some misread the advice. Some think that they should get an A+ if they make each change suggested.

It's a messy exchange. The students have 'the-paper-they-think-they-wrote' in mind. I have a goal I want the students to aspire towards. The papers they write say one thing, but those papers are in the process of becoming something else.

It is a setting rife with opportunities for misinterpretation.

Getting Through Feedback

Getting Through Feedback

The second issue is more mundane. When I am sitting at home with a stack of papers to comment on, there is a temptation to spend the day on

Reddit, or

Facebook, or

Kongregate, or

anywhere else that isn't the next twenty drafts of essays waiting for comments.

My solution involves bringing the student in on the process.

Here's what I do

I ask my students to throw the text of their drafts onto a Google Drive Document. I tell them not to worry about lost formatting - as this is just a draft.

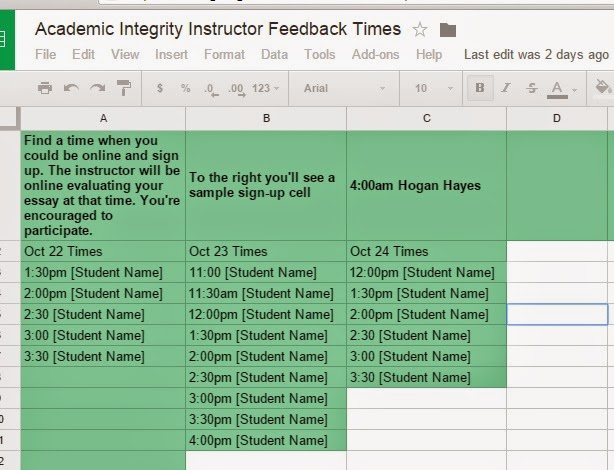

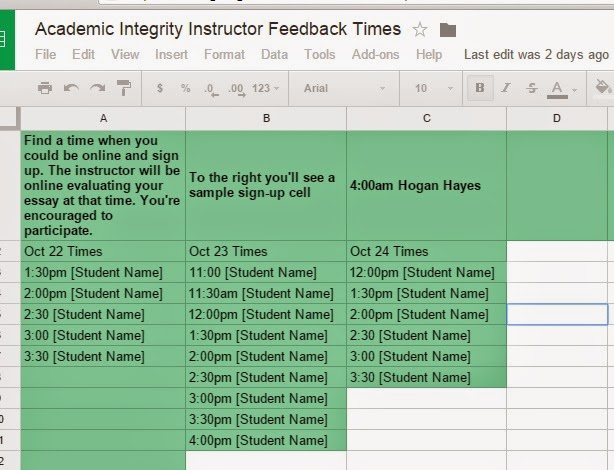

Then I ask them to pick a time when they can be online along with me.

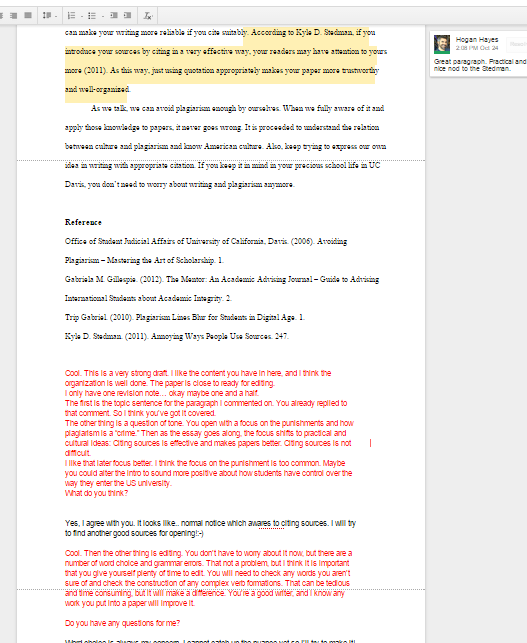

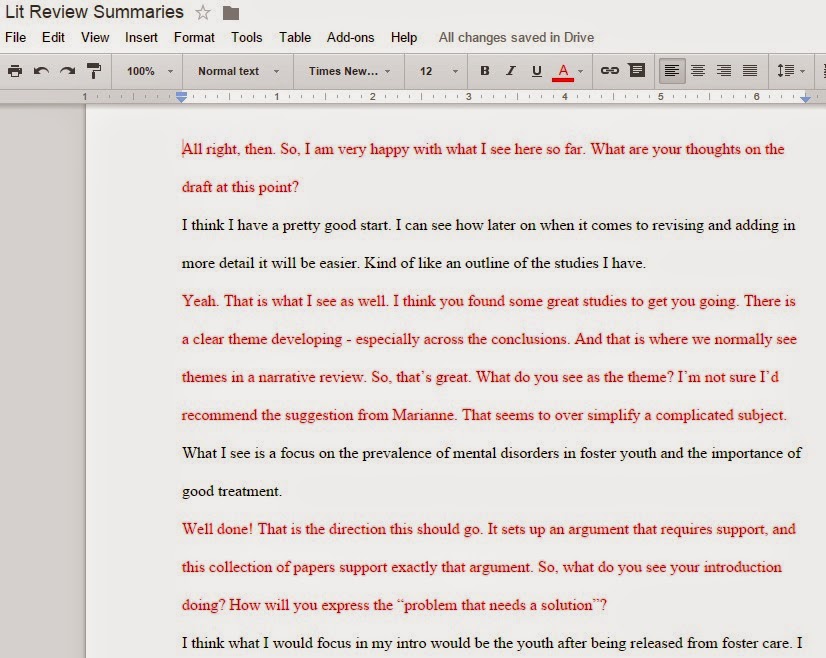

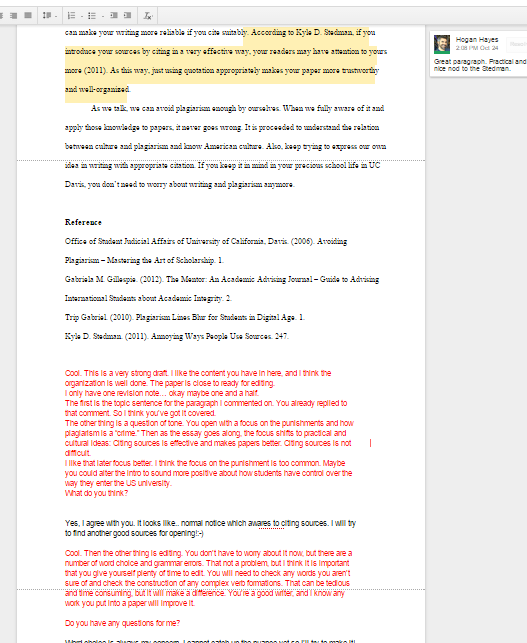

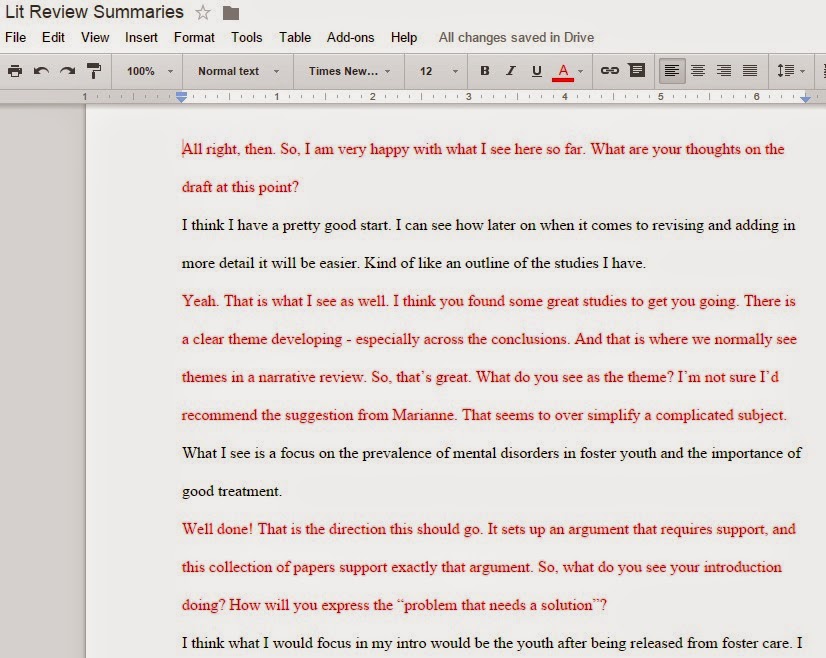

At the appointed time, we both go to the document. The student can see my comments as I post them, and any edits I make happen in "real time."

I comment on their papers while they're watching, and I invite them to respond to my comments as we work.

...and that's it really.

It sounds simple, and it is. The initial set up is a bit tricky, but I have small courses this term. That's made the piloting of this a lot easier.

With a scheduling spreadsheet open to the group, sign ups are easy enough. I give most students about 20 minutes of time. I give 30 minutes to L2 writers (students writing in their second language).

And I let Google Drive do the the technical work. I'm sure there are other platforms that could support this, but I just went with what was easiest for my students to access.

I can see this becoming something I research and write about in the near(ish) future, but for now I'm just hammering out the details.

I'd appreciate any thoughts or suggestions from my friends in composition and rhetoric.